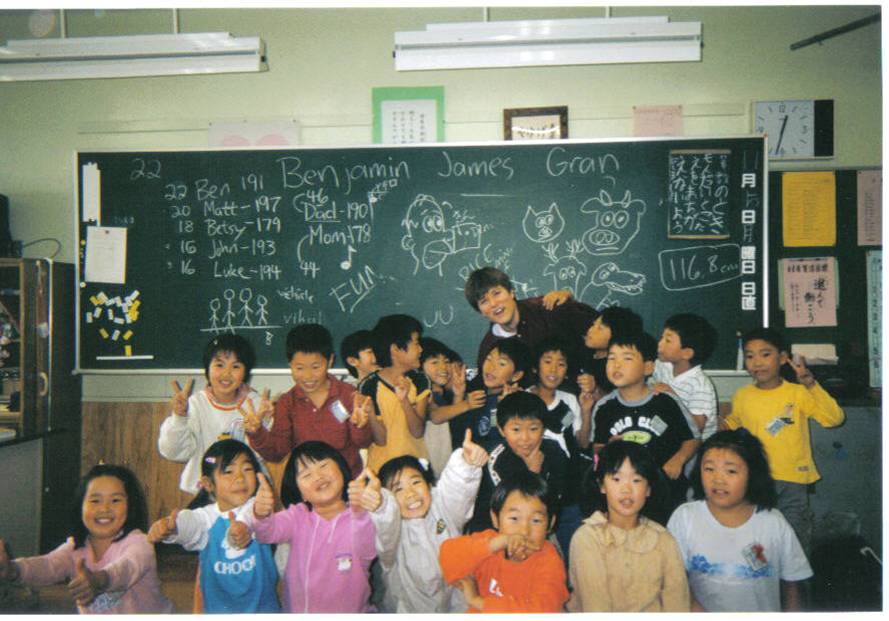

My first job out of college was teaching English in Japan on the JET Program (“Japan Exchange and Teaching Program”) back in 2001-2002. That year of living in Japan and teaching in the Japanese public schools was one of the most influential years of my life, and it was an ideal adventure for that time in my life, when I was single and hadn’t started on a rigid “career path” and had the freedom to travel and be an interloper in another country. I made wonderful friends in Japan that I’m still in touch with today. Living in Japan gave me a sense of perspective and broader awareness of the reality of the world beyond America – it helped me see the beauty and uniqueness of other cultures in a new way, and it has affected my decision making and sense of identity in many ways.

My experience living in another country taught me not to take America too seriously – I know – really know, on a fundamental level – that the world is bigger than this one country and that there is more than one way to solve problems and interpret situations. At the same time, living in Japan taught me to appreciate a lot of things about America that I had previously taken for granted – even while I admired many things about Japan that are unique to Japan’s cultural context. Teaching English in Japan gave me a new understanding of myself, my place in the world, and my appreciation for my fellow human beings.

If you want to teach English in Japan, working on the JET Program is one of the best ways to do it. I highly recommend the JET Program to anyone who’s looking for a fun adventure and who’s interested in teaching English in Japan. It’s a great opportunity that continues to benefit you as a person for years after it’s over.

A few years ago, a friend of a family friend contacted me with some questions about the JET Program. She was wondering about the realities of teaching English in Japan. I have enclosed her questions – and my answers – below:

What motivated you to go teach English in Japan on the JET Program?

I didn’t know what else to do after I graduated from college, and nothing else sounded good. I had a strong desire to have the experience of living in another country (I never studied abroad). I had some good friends from Japan who I had met at college by signing up to be a conversation partner in the ESL program, and so that helped make the decision. Plus one of my other good friends from college grew up in Okinawa, and he and I had talked a lot about Japan, and it all sounded pretty good.

Why did you choose to apply for the JET Program?

The JET Program was only a one-year commitment (as opposed to the Peace Corps or other types of programs that are a multi-year commitment), and it was an actual “job” with a paycheck; no research papers required. As for how JET compares to other options for teaching in Japan, the JET program generally pays better (my salary at the time was around $30,000 per year, tax-free), the JET program gives you more time off (I think I had like 4 weeks of time off), they help you find an apartment (which is a HUGE benefit in Japan, where there are a lot of hard-to-understand rules and customs for renting a place), and JET allows you to teach in the public schools during regular work hours, as opposed to the “eikaiwa” (English Conversation) schools where you often teach at night and on weekends. I’ve also gotten the impression that JET Program teachers tend to have an overall better “quality of life” on the job – fewer contact hours, more unstructured time, more time to study Japanese, etc. I’ve heard that a lot of the Eikaiwa schools just keep lining up one student after another with little time to decompress.

But you know what, I think the #1 factor that sold me on the JET Program was that they helped you get your own apartment. It sounds stupid now, but at the time, at age 21, I had lived in the dorms for all 4 years of college, so getting my own apartment sounded really daunting. I remember going to an orientation session for the JET Program and they played a video showing the nice cozy apartments in Japan where some of the JET teachers lived, and I was like, “Wow! My own apartment? Sign me up!”

Do you think it’s OK to choose a program other than JET for teaching English in Japan?

Yes. In fact, I know several people who taught for private eikaiwa schools (like Nova and GEOS), and they had a generally good experience. But I had no regrets doing the JET Program – I think it’s probably the best way to teach in Japan.

Did you go with someone you knew?

I knew no one. But I found that it was quite easy to make friends with other people on the program. I made friends with lots of my JET Program colleagues from Canada, Australia, Britain and America, and also made friends with lots of Japanese locals. There were always people to talk to and hang out with and go drinking with. I really had quite an active social life in Japan – more active than my life in America once I got back. Plus I was VERY fortunate to have a built-in circle of friends in Tokyo via my ESL conversation partners – I still keep in touch with those friends 12 years later, and my wife and I visited my Japanese friends in Tokyo in February 2007.

What were the biggest difficulties you encountered?

The language barrier. (I spoke no Japanese when I arrived – but I learned fairly quickly.) The hardest thing on a day-to-day basis was not understanding the background noise of daily life – I was basically illiterate over there. (Although Japan makes it easier, since the train station signs and bus stops and public locations are in English letters (“romaji”)). I really missed being able to go to a public library and read anything I wanted, in my own language. It was strange not being able to read anything over there – for example, the subways and trains would be covered with ads and posters, and I wouldn’t be able to read what they were for. (“Is this an ad for a car company or for rat poison? I can’t tell…”)

Certain things about working in another culture were hard – teaching on the JET Program was my first “real” job post-college, and I probably made all kinds of mistakes that I’ve forgotten about or forgiven myself for by now.

Some of my mistakes included:

- I used to eat breakfast at my desk, which is a no-no. I didn’t intend to be disrespectful, but by eating at my desk, I was showing disrespect to the other “real” teachers who got to work earlier than I did and had already eaten breakfast. (I am not a morning person.)

- I used to be late for school sometimes. Punctuality is highly prized in Japanese culture, so I was really screwing up on that front as well.

- I once flooded my downstairs neighbors’ apartment when I forgot to put the drainage hose from my washing machine into the drain in the shower (long story – fortunately nothing was seriously damaged, and it turned out that I had accident insurance through my employer).

- Some people on the JET Program occasionally have a bad attitude about work – lots of whining about JET Program policies, complaints about the boss, etc. It’s natural to feel frustrated with things at work, but in retrospect our lives on the JET Program were much, MUCH better than they would have been at almost any entry-level job back in our home countries. I wish I had complained less and learned more and studied harder.

One thing I learned from teaching English in Japan is that culture shock is definitely real. Except “culture shock” isn’t the right term for it, it’s more like “culture fatigue.” There are certain things about living in another country that just start to wear on you after awhile, especially where the culture is so different from your own. Certain small things start to feel annoying or oppressive – for example, I remember being on the train one Sunday afternoon, riding into Tokyo, and seated across from me was a group of middle-aged women on a weekend outing, chatting amiably together. And they were all wearing the same style of hat – kind of an inverted flowerpot shape that was popular in Japan at the time. And I remember thinking to myself, “Oh, come on – do you all really have to wear exactly the same sort of hat???” And really, how unfair of me to feel annoyed about their hats! They were just minding their own business. But that’s the kind of thing I remember as being difficult – just little reminders of the cultural barriers between me and the rest of the people there. There were times when I felt very alone.

Earthquakes – that was a big challenge for me. Japan gets LOTS of earthquakes, and I’m from a part of the U.S. that never gets earthquakes, so the occasional earthquakes really freaked me out – I would wake up in the night and the walls of my building would be trembling, dishes rattling in the cupboards. Not fun.

I also experienced a fair amount of homesickness, I suppose – I always enjoyed talking with my parents on Sunday nights. I would call them at 9 p.m. from Japan, which was 7 a.m. Iowa time, and we would talk for an hour or so. Another thing that was hard was that my grandpa died while I was in Japan, and I wasn’t able to come back for the funeral. So that’s definitely something to think about – if you live abroad, you might have to miss out on some friends’ weddings, births of new family members, funerals or other life events.

Another difficulty was the work itself. The job of being an Assistant English Teacher could occasionally become very boring. The overall “experience” was really an amazing privilege – being able to work in another country’s public school system and talk with the kids all day – but the day-to-day “work” wasn’t always that challenging, if that makes sense. I suppose it’s my own fault – looking back on it now, I could have done much more to learn Japanese, get involved with the other teachers, plan lessons, etc. While listening to the other teachers speak rapid-fire Japanese during the morning staff meeting, I should have been taking notes, writing down words that I recognized, and looking them up in my dictionary, building my vocabulary. I should have tried harder to learn more every single day. I should have been more of a “sponge for knowledge.”

And I should mention – most of the teachers that I worked with were really great. They helped me a lot, they involved me in the classes, they tried to make things fun for the students. But a lot of days, I just felt like I was kind of “in the way” or that I didn’t understand any of the conversations going on, and I just kind of let things happen around me without being as engaged as I could be. (This is probably making me sound like a terrible employee – I’m really not that bad.) But that was hard – those days when it felt like less of an exciting adventure, and more like an unchallenging job. (Of course, there are lots of times as a working adult in the U.S. where you’ll feel unchallenged or unfulfilled by your job. There have been times as a grown-up person in America where I’ve wondered if I should move my family back to Japan and go back to teaching English! But now that I’m a freelance writer, I’m quite happy with my career.)

Feelings of isolation, homesickness and culture shock come and go. There were times when I didn’t feel like a “real” person in Japan – like this was just a temporary stopping point and I wasn’t really building anything that would last. It’s liberating to be an interloper, but sometimes you want to feel like you’re putting down roots and are more authentically connected to a community and a place. But there are also a lot of incredibly exciting, invigorating, inspiring aspects to living in another culture, and the good far outweighed the bad in my experience.

Was it hard coming back to the U.S. after teaching English in Japan?

It was very, very, very hard. I came back after a year (actually only ten months) to take a job at the Governor’s office in my home state of Iowa – it was a pretty special job opportunity and I had to come back early from Japan in order to start my new job. But to my surprise, coming back to America was harder than going to Japan. The “reverse culture shock” was harder in every way. I missed Japan a lot, I missed my friends and my carefree life over there, I missed riding the trains and riding my bike and walking everywhere and not having to use a car, I felt regrets for having come back so soon, I wondered if life would ever feel quite so exciting or interesting again. (It probably didn’t help that I was living at home with my parents for the first seven months after coming back to the U.S.) Life just seemed so…colorless back in my home country. I probably was depressed, on some level.

To get over my sense of reverse culture shock, I read a lot of books about Japan – Haruki Murakami is one of my favorite authors – and I corresponded with my friends, and in time I got better. Eventually I was able to build a life for myself in the U.S. that was fun and fulfilling. But it took a long time – it took like a year to get over the reverse culture shock. I think I had reverse culture shock for longer than I actually lived in Japan. It’s funny – now that I’m thinking about all this again – I remember that the decision not to renew my contract on the JET program was a really hard decision. I was literally physically sick about it. In a lot of ways, the JET Program was a good job, and people there treated me very well, and I’d had this great cultural experience, and I thought, “are you sure you want to give all this up?” So that was a big decision, the moment when I decided not to stay on for a second year. I think it was February when we had to decide that. And then I ultimately found my new job and decided to come home in May.

Would you suggest taking a shorter teaching trip to sort of “test the waters” of working abroad?

I don’t know what options are out there – I think it’s easier to get a visa if you’re committed to going over there for a full year. But I could be wrong. The plane ride is so long (14 hours Chicago to Tokyo, each way) and expensive, and the experience is so great once you get over there, that I really think it’s best to just take the plunge and commit to going over for a year. It probably makes things easier as far as leaving behind your life in the U.S., too.

Have you traveled anywhere else in Asia?

No, and that is the one regret of my time in Japan. I was only there for 10 months, and I originally thought I would be there longer – 2 years, 3 years maybe. But instead I wound up coming back to Iowa after only 10 months, and I never traveled elsewhere in Asia. I didn’t even travel in Japan very much, I mostly hung around in Tokyo with my friends. (Of course, there’s a lot to see in Tokyo – it’s the biggest city in the world.) Some of my colleagues on the JET Program took great vacations to Thailand, Korea, China, Hong Kong and many other places – and it’s so much cheaper to fly to other destinations in Asia once you’re in Japan.

What was the JET Program application process like?

Long, but not too tough. If I remember correctly, the application deadline was December, and then we interviewed in…March? And then got acceptance letters in April, and flew to Tokyo at the end of July. So it was an eight month process, start to finish. I’ve read/heard that it used to be a lot faster to get signed up to teach in Japan with Nova or GEOS or other eikaiwa schools, but I don’t know if this is still the case with the economy the way it is now. It’s also possible that the JET program has become more selective since I was on it.

Was it hard to make plans for the next year when you were waiting to find out if you’d been accepted?

At the time, I was a senior in college, and I didn’t have many other career plans. It was pretty much a choice between doing the JET Program and moving back to my parents’ basement. (I had some job interviews with consulting firms in the U.S., but no job offers.) So I pretty much pinned all my hopes on going to the JET Program, and fortunately it worked out for me. My senior year of college was a rather emotionally tumultuous time, but not because of the JET Program; I had my own reasons for all the tumult. I was just generally struggling to figure out what (if anything) I wanted to do with my life after graduation, and in my darker moments, I felt like no matter what I chose, it would be wrong. And I had recently ended my first really really serious romantic relationship, so I felt like I was going out into the world after college feeling completely adrift.

Of course, looking back on it now, there is no “wrong” plan. As long as you have something that you want to pursue, even if it’s only one thing – and you pursue it with integrity and hard work, good things will happen.

I’m grateful for the JET Program for giving me a good start to adult life and introducing me to so many wonderful people. I’d recommend it to anyone who wants to have an adventure.

Are you interested in teaching English in Japan on the JET Program? Feel free to send me any questions via e-mail and I’ll be happy to respond: benjamin.gran@gmail.com